WE BELIEVE IN DATA’S POTENTIAL TO FACILITATE

RECKONING & REDRESS

In recent decades, data has exponentially increased our understanding of slavery and its legacies.

Much of this data represents years or decades of hard work by scholars and professional archivists. For example, since 2015, THFI Co-Founder Jennie K. Williams, Ph.D. has built three databases collectively containing information about approximately 70,000 enslaved ancestors.

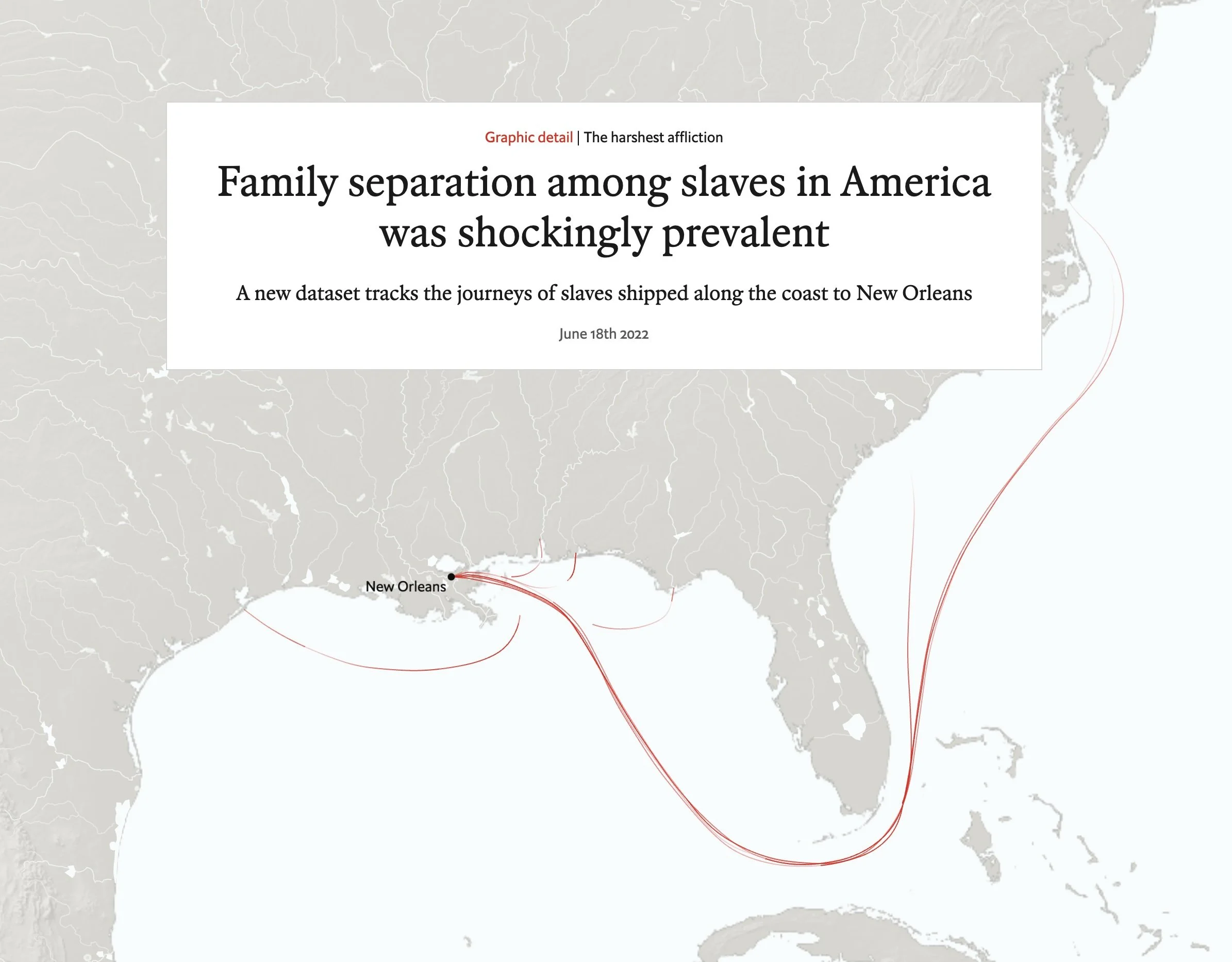

OCEANS OF KINFOLK includes the names of more than 63,000 enslaved men, women and children trafficked to New Orleans from domestic ports between 1818 and 1860. Based on thousands of ship manifests, Oceans of Kinfolk is the largest existing database of the domestic slave trade, and of enslaved ancestors’ names generally.

LOUISIANA KINDRED is a developing database of enslaved individuals who were bought and sold in New Orleans, the nation’s largest slave market. Louisiana Kindred is based on thousands of notarial records of sales of enslaved persons.

NAMED IN AFFECTIONATE TERMS is a database containing information about the individuals and families enslaved by the Carrolls of Maryland between 1689 and the Civil War. Named in Affectionate Terms is based on hundreds of records, including plantation ledgers, estate inventories, advertisements for fugitives from slavery, and bills of sale.

Other groundbreaking achievements in slavery’s data include…

Launched in 2019, Freedom on the Move is the largest online repository of digitized newspaper advertisements for fugitives from slavery. At current count, the site contains information about more than 30,000 freedom-seekers.

The Legacy of Slavery in Maryland is a project by the Maryland State Archives focused on digitizing records related to the state’s free Black and enslaved population. The project has produced a searchable database including information about more than 400,000 individuals “including, white and black, slave owners, enslaved and free individuals.”

Data built from slavery’s historic archive has three main uses.

1. KINSEARCH

Because enslaved people were legally prohibited from learning to read or write, relatively few were able to leave behind written records of their lives. What’s more, enslaved people do not appear in records—federal censuses or city directories, for example—where descendants of free people can find information about their ancestors. For these reasons and others, most records of enslaved people’s lives were written by enslavers. Even so, when made accessible as data, these records provide precious information about enslaved ancestors.

Darron E. Patterson, Descendant of Clotilda survivor Kupollee Allen.

2. RESEARCH & RECKONING

Large datasets are uniquely capable of providing powerful answers to history’s biggest questions. For example, Oceans of Kinfolk allowed Dr. Williams to produce a new estimate of the violence inflicted on African American families during slavery: She found that 88 percent of individuals trafficked to and sold in New Orleans, the nation’s largest market for buying and selling human beings, were separated--most often permanently--from their entire families in that process.

3. EDUCATION

Data is an increasingly important teaching tool for K-12 & college educators. Since 2022, the American Library Association has reported a record-breaking number of attempts to ban books addressing the history of slavery and its legacies each year. Thus far, few digital history projects have suffered the same fate. Data, in other words, is frequently permitted in classrooms where other pedagogical resources are not.

Matthew Leibensperger, Carroll County, MD high school teacher.

But there is so much work left to do.

At present, only a fraction of slavery’s global archive has been digitized, and an even smaller portion is freely accessible as searchable data.

Hundreds of thousands of records—documents containing information about millions of enslaved ancestors—await rediscovery. Many haven’t been touched since they were created roughly two centuries ago. Where are all these records?

Some are stashed in dusty attics above abandoned houses. Many are filed away in university archives, while many more sit in unlabeled boxes in courthouse basements.

Slavery’s archive is everywhere. Unless its records are preserved and made accessible, however, it might as well be nowhere.